With the recent popularity of the the film “Oppenheimer”, I was curious as to where the world’s first nuclear reactor would have been located. It’s amazing the information you can find by doing a simple Google search. It seems that with proper funding, more time and purer materials, the first man-made nuclear chain reaction would have taken place in Ottawa. A scientist working at he National Research Council in 1940 by the name of George C. Laurence made the first experimental nuclear reactor in 1940.

A year later, the Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) became the world’s first successful artificial nuclear reactor. On December 2nd, 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in Chicago with the CP-1 reactor.

A year earlier, another reactor was initiated in Ottawa, but lacked the proper materials to be completely successful. Dr. Laurence joined the staff of the National Research Council of Canada in 1930 and became active in improving the measurement of radiation dosage in the treatment of cancer and in promoting safety from radiation exposure, but also became instrumental in creating nuclear energy.

With the world superpowers entrenched in a World War, the Commonwealth country of Canada seemed like an unlikely candidate for creating nuclear power, but like most technological advancements, Canada persevered and was a pioneer in the field.

Research in the National Research Council of Canada during WW2 was focused on wartime efforts to advance allied technology against the Axis powers, and one such avenue of research was that of nuclear energy.

Dr. Laurence in Ottawa in 1940 surmised in his spare time that a very large number of fissions produced in a reaction would release a large amount of energy. There was evidence to show that a large increase in the rate of producing fissions would be easier to accomplish if the neutrons were moving slowly. They would move more slowly if they encountered large numbers of very light atoms such as hydrogen atoms; therefore, it might be advantageous to associate with the uranium a suitable quantity of material containing hydrogen, such as water. Heavy Water.

By this time however, the nuclear scientists in England and the United States had stopped publishing the results of their research, and continued their work in secrecy. With heavy water extremely scarce and hard to produce, Laurence decided to try and use just basic carbon instead of heavy water in his nuclear reactions, as it was cheaper and easier to produce.

So, in Ottawa, between 1940-42, Laurence decide to create his own “Nuclear Reactor” using carbon powder instead of heavy water.

Here are the actual experiment notes from Dr. Laurence on what was likely the world’s first nuclear reactor experiment that occurred in Ottawa:

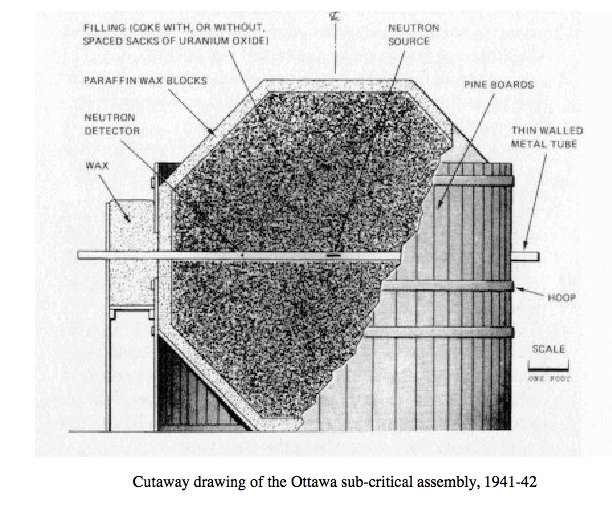

“In our experiments in Ottawa to test this, the source of neutrons was beryllium mixed with a radium compound in a metal tube about 2.5 centimetres long. Alpha particles, emitted spontaneously from the radium, bombarded atoms of beryllium and released neutrons from them. The carbon was in the form of ten tonnes of calcined petroleum coke, a very fine black dust that easily spread over floors, furniture and ourselves. The uranium was 450 kilograms of black oxide, which was borrowed from Eldorado Gold Mines Limited. It was in small paper sacks distributed amongst larger paper sacks of the petroleum coke.

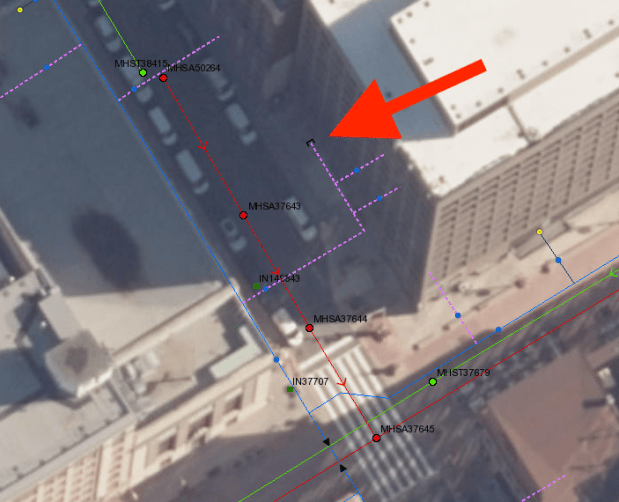

The sacks of uranium and coke were held in a wooden bin, so that they occupied a space that was roughly spherical, 2.7 m in diameter. The wooden bin was lined with paraffin wax about five centimetres thick to reduce the escape of neutrons. The arrangement is shown above, as a sectional view through the bin and its contents.

A thin wall metal tube supported the neutron source at the centre of the bin, and provided a passage for insertion of a neutron detector which could be placed at different distances from the source. In the first tests the detector was a silver coin, but in most of the experiments it was a layer of dysprosium oxide on an aluminum disc.

The experimental routine was to expose the detector to the neutrons for a suitable length of time, then remove it quickly from the assembly and place it in front of a Geiger counter to measure the radioactivity produced in it by the neutrons. The Geiger counter tubes and the associated electrical instruments were homemade because there was very little money to spend on equipment.”

By 1942, Laurence realized that the nuclear energy released was too small because there was too much loss of neutrons by capture in impurities in the coke and uranium oxide and in the small quantities of paper and brass that were present. These little impurities could lead to failure, and the American and British research teams took over the experiments using more refined materials.

It was in 1942 after these initial Ottawa nuclear experiments that is was decided that a special unit of nuclear research would be set up in Montreal.

On September 2, 1942 Canada received scientists from England, and was provided laboratory facilities and supplies and administer the project in Montréal as a division of the NRC.

The first of the staff from England arrived about the end of the year 1942 and set up shop at 3470 Simpson Street belonging to McGill University. Three months later, they moved into a 200 square metre area in the large, new building of the University of Montréal, and more scientists and technicians arrived from England.

The Project became part of the Manhattan Project and with great enthusiasm, a Canadian group of scientists were brought together with a single purpose…to create nuclear energy.

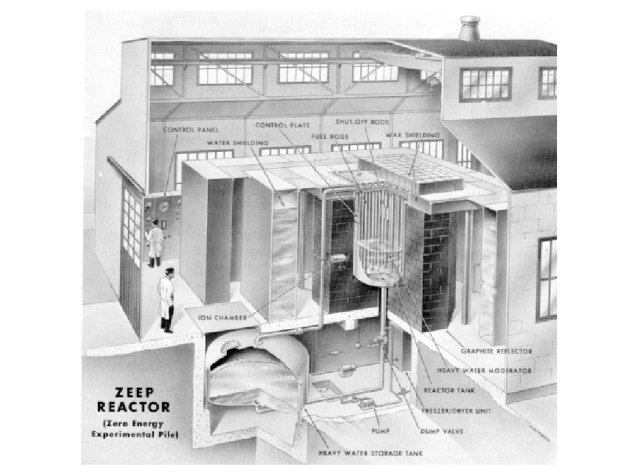

Building reactors in downtown Montreal was out of the question; so the Canadians selected a site at Chalk River, Ontario, on the south bank of the Ottawa River some 110 miles (180 km) northwest of Ottawa.

This is where Canada’s first operational nuclear reactor was born, called “ZEEP”. The Chalk River Laboratories opened in 1944, and the Montreal Laboratory was closed in July 1946 when the Chalk River reactor went critical on September 5th, 1945, becoming the first operating nuclear reactor outside the United States.

Andrew King, September 26th, 2023

SOURCES

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montreal_Laboratory

https://www.cns-snc.ca/media/history/early_years/earlyyears.html