Samuel deChamplain’s 1632 map of the East Coast.

Samuel de Champlain’s map of 1632 refers to a tributary in Miramichi Bay as “Crow Brook”. This is what is now known as “French Fort Cove” because at its mouth on the western bank, known as Kethro lookout, it was the site of a French battery in 1756. It is curious that Champlain on more than one occasion has appeared on the scene in the footsteps of previous explorers, in this case the Norse, who likely settled in the Miramichi area.

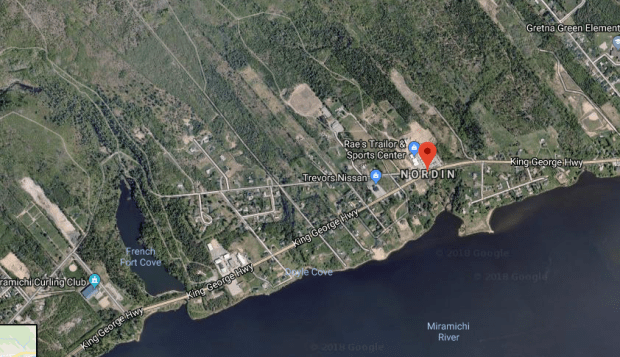

French Fort Cove and Nordein marked on Google Maps.

It is also curious that the area known as French Fort cove fits the description of Hop from the Norse sagas. It has a hill where the settlement was built (other parts of Miramichi towards the coastal area is relatively flat), has a protected harbour area, and a stone cliff that is mentioned in the sagas where they battled the natives. A flowing brook would have been full of salmon, also mentioned. Wild grapes grow in the cove on its hills. A few hundred metres from this area the village of “Nordin” exists, a Nordic name. Coincidence perhaps.

An arrangement of four cut stones at French Cove. Date unknown.

Stone cleared off with scribed marks.

Amazingly, I stumbled upon the abandoned 1800s quarry used to provide the stone for Langevin Block (Prime Minister’s Office) in Ottawa.

A brief exploration of the area turned up some interesting finds, but it is unclear the age of these historic artifacts. They could be quite possibly be remnants of the 1700s French Fort that was there.

Another search occurred at Oak Point, as oak was revered by the Norse for its boat building use. This did not fit the description. Also checked out was Burnt Church, a place near the mouth of the river that housed a 1600s French missionary, later burnt down by the British. This also fit the description, but is an active reservation for the Burnt Church First Nation Mi’kmaq. The Norse likely traded with the Mi’kmaq, but relations turned ugly and the two battled often, a possible reason for their departure.

Carved stone found at Burnt Church, ‘IHS” and the cross. “In Hoc Signo” a Latin phrase meaning “In this sign you will conquer”

We have a very specific timeline of history regarding our first overseas visitors to Canada. History tells us the Norse Vikings from Iceland via Greenland came around 1000AD, then John Cabot in 1497AD. That is almost a 500year gap. So we are to believe that in those 500 years no one came over to Canada…no one at all? I find this very hard to believe.

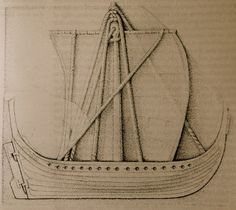

The Norse were on the eastern coast of Canada in 1000AD, so the possibility exists someone else did it in the 500 year gap between them and Cabot. We know that the “Cog” ships were of a more advanced construction than the Nose Knarr boats, which we know made the journey. Northern Europe had such ships during the medieval era that would ply the Atlantic full of trade goods. A cog is a type of ship that first appeared in the 10th century, and was widely used from around the 12th century on. Cogs, and their sister ships, the birlinn, were clinker-built, generally of oak. They resembled and were constructed very similarly to the Norse knarr ships, probably due to the fact that the Norse and Scots were close in both proximity and relations at that time. Sharing stories of exploration and ship building technology would have been common.

Fitted with a single mast and a square-rigged single sail, these vessels were mostly associated with seagoing trade in medieval Europe and ranged in length from about 15 to 25 meters (49 to 82 ft) with a beam of 5 to 8 meters (16 to 26 ft), and could carry up to about 200 tons of cargo.

Cogs had a flat bottom at midships but gradually shifted to overlapped planks near the bow and stern. Caulking of hull planks would have been tarred moss that was inserted into curved grooves, covered with wooden laths, and secured by metal staples called sintels. Using a a stern-mounted hanging central rudder (which was a unique northern development) to steer. These ships were the most common vessels of the medieval era and would have made long distance trips. It would not be stretch that these vessels would hopscotch between islands of northern Scotland/Ireland, over to Greenland and Iceland, with Canada being almost the same distance between those aforementioned areas.

It is curious to see flying here in Miramichi that the provincial flag of New Brunswick illustrates a medieval trading vessel called a “lymphad”. Used primarily in Scotland, a wooden vessel propelled by sail and oars, traversed the Highlands and was used to sail west in the Hebrides during the 1100s-1500s. The flag of New Brunswick took the old ship symbol and made that lymphad the prominent feature. An interesting choice indeed!

A painting depicting Columbus in Iceland in 1477 getting directions to America.

We also know that the Norse kept tales of the new lands they discovered alive because in 1477 Christopher Columbus visited them to get that information from them. Arriving in Iceland and living at a farm called Ingjaldshóll, Columbus learned about the former Norse settlement in Vinland, and how the Vikings sailed to a New World, and about the travels of Leif Eiríksson and the rest of the Norse who had already been to North America five centuries earlier.

Columbus is credited because his “discovery” was celebrated and recorded with great pomp and circumstance, yet the Norse voyage to America was only made known when there was proof in 1960 after L’anse Aux Meadows was dug up. So what evidence do we have of another possible trip to Canada by another group of seafarers in the Northern Atlantic? That group, who heard tales from their Norse neighbours and trading partners most likely arrived here during the 1300s and I think that evidence of their arrival lies on an island in Mahone Bay off Nova Scotia. Someone followed in the footsteps of those original Norse settlers that spun tales of their old adventures and prompted some very curious people to arrive at Oak Island for their own reasons which we will soon discover.

Andrew King, May 25th, 2018

Your research is nicely narrated and well illustrated with photos, maps and paintings. Keep up the great work.

Dear Andrew,

You write that, “It is also curious that the area known as French Fort cove fits the description of Hop from the Norse sagas.”

It looks like the Miramichi River would have been realistically the type of place that the Vikings would have visited. For instance, butternuts are found far up the Miramichi River at Doaktown, and this is as far northeast as they grow. But I am not sure how navigable the Miramichi River would have been for the VIkings that far up the river. Additionally, Butternuts were found at the L’anse aux Meadows Viking site in Newfoundland.

On the other hand, the Vikings’ settlement in the Greenlanders’ Saga that would fit the St Lawrence Gulf southwest of L’anse aux Meadows was described as being by a lake, and there is no such lake, literally speaking, at the Miramichi River. Perhaps some bulky part of the River could have been imagined of as a “lake”, I suppose.

I drew charts and collected scholars’ maps as to how those 4 sites would look if the Sagas’ directions to them were taken literally, and discussed them here:

historum.com/t/where-do-the-viking-sagas-point-to-the-vikings-visiting-in-the-us-or-southeast-canada.196378/